Australian Libertarian Community

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

🗳️ The "Voice"

- Thread starter Conza

- Start date

I am not following this Conza. I did read the mailout from the AEC and the Yes proposal seemed very vague. Apart from being nice to aboriginals there didn't seem to be any concrete proposals. Inevitably it will result in a new plague of bureaucratic rent seekers bleeding us dry and nothing will improve.Interested in your critiques & comments on the upcoming referendum.

None of the critiques I've seen address any of the underlying issues—not from a libertarian perspective anyway. The "no" campaign isn't offering anything 'positive' in terms of any rebuttals. The risk is even with any successful 'no' rebuttal it still leaves the premises of the "YES" campaign [socialist approaches] as untouched & still standing:

I would start with questioning the premise of sovereignty. You can't just rock up to an entire continent and lay a justifiable claim to it. Not by any reasonable measure.

1) Not going to dive into it in any length but given the concept of self-ownership; the state isn't justifiable - Monarchs rule etc.

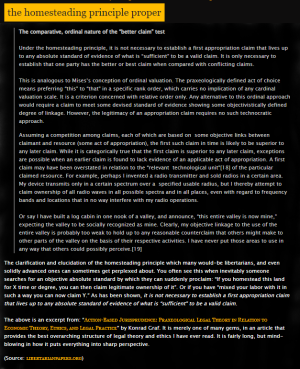

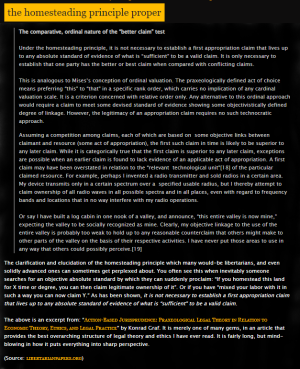

2) Given the first appropriation principle, or the homesteading principle proper:

So, what has the better claim?

Whilst any sovereign claims aren't ever going to be valid (their existence is the product of institutionalised aggression/theft) — normal civilian/local native ones aren't either if they constitute the equivalent of e.g.

Additionally it goes without saying institutionalised aggression against local natives/free settlers that wasn't self defence was/is also unjustifiable.

In principle — reparations are valid upon the basis of the following:

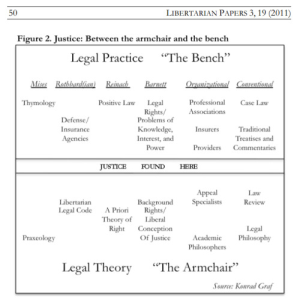

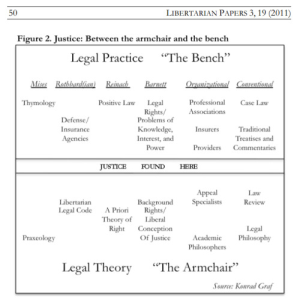

With these important principles (legal theory "armchair") established — what about legal practice "the bench"?

This acquires assessing the merits of the individual case/claim based on the evidence — who has the better claim (amongst competing ones?)

34m53s - 37m47s

The longer time goes on, the harder it often is to prove causal linkage. Given that possession is "9/10's of the law" and that the burden of proof lies on that attempting to prove otherwise.

There's no 'collective' rights either, anyone claiming a right to X also based on them being the same race is a racist—by definition.

Further, the extensive amount of land with such an incredibly sparse population 200+ years ago, almost all initial legitimate land claims would have been over currently unclaimed land... and were justly/voluntarily acquired and homesteaded.

At best though, there might have been easement rights granted for those who passed through and hunted etc. on that land, which shouldn't have been disturbed/maintained.

Would be interested in any commentary or things that might have been missed.

An “anti-something” movement displays a purely negative attitude. It has no chance whatever to succeed. Its passionate diatribes virtually advertise the program that they attack. People must fight for something that they want to achieve, not simply reject an evil, however bad it may be. They must, without any reservations, endorse the program of the market economy.

— Ludwig von Mises, Anti-Capitalist Mentality, Chapter 5.

I would start with questioning the premise of sovereignty. You can't just rock up to an entire continent and lay a justifiable claim to it. Not by any reasonable measure.

1) Not going to dive into it in any length but given the concept of self-ownership; the state isn't justifiable - Monarchs rule etc.

2) Given the first appropriation principle, or the homesteading principle proper:

So, what has the better claim?

Whilst any sovereign claims aren't ever going to be valid (their existence is the product of institutionalised aggression/theft) — normal civilian/local native ones aren't either if they constitute the equivalent of e.g.

Or say I have built a log cabin in one nook of a valley, and announce, “this entire valley is now mine,” expecting the valley to be socially recognized as mine. Clearly, my objective linkage to the use of the entire valley is probably too weak to hold up to any reasonable counterclaim that others might make to other parts of the valley on the basis of their respective activities. I have never put those areas to use in any way that others could possibly perceive.[19]

Additionally it goes without saying institutionalised aggression against local natives/free settlers that wasn't self defence was/is also unjustifiable.

In principle — reparations are valid upon the basis of the following:

“Suppose that centuries ago, Smith was tilling the soil and therefore legitimately owning the land; and then that Jones came along and settled down near Smith, claiming by use of coercion the title to Smith’s land, and extracting payment or “rent” from Smith for the privilege of continuing to till the soil. Suppose that now, centuries later, Smith’s descendants (or, for that matter, other unrelated families) are now tilling the soil, while Jones’s descendants, or those who purchased their claims, still continue to exact tribute from the modern tillers.

Where is the true property right in such a case? It should be clear that here, just as in the case of slavery, we have a case of continuing aggression against the true owners-the true possessors-of the land, the tillers, or peasants, by the illegitimate owner, the man whose original and continuing claim to the land and its fruits has come from coercion and violence. Just as the original Jones was a continuing aggressor against the original Smith, so the modern peasants are being aggressed against by the modern holder of the Jones-derived land title.

In this case of what we might call “feudalism” or “land monopoly,” the feudal or monopolist landlords have no legitimate claim to the property. The current “tenants,” or peasants, should be the absolute owners of their property, and, as in the case of slavery, the land titles should be transferred to the peasants, without compensation to the monopoly landlords.”

— Murray Rothbard, The Ethics of Liberty, Chp 10 -The problem of land theft

With these important principles (legal theory "armchair") established — what about legal practice "the bench"?

This acquires assessing the merits of the individual case/claim based on the evidence — who has the better claim (amongst competing ones?)

The longer time goes on, the harder it often is to prove causal linkage. Given that possession is "9/10's of the law" and that the burden of proof lies on that attempting to prove otherwise.

There's no 'collective' rights either, anyone claiming a right to X also based on them being the same race is a racist—by definition.

Further, the extensive amount of land with such an incredibly sparse population 200+ years ago, almost all initial legitimate land claims would have been over currently unclaimed land... and were justly/voluntarily acquired and homesteaded.

At best though, there might have been easement rights granted for those who passed through and hunted etc. on that land, which shouldn't have been disturbed/maintained.

Would be interested in any commentary or things that might have been missed.

Walter Block recently wrote this as well: https://www.econlib.org/who-really-owns-the-united-states/

And I came across:

Looks like it's 15% now public, but note:

So not allowed to use for anything other than that (land can't be used for housing).

TL;DR

85% of Australias land mass basically not available for housing/private ownership.

10.5% private. 4.5% unknown.

* "About 40% of Australia is covered by native title, in both exclusive and shared title."

** "When non-exclusive native title is included, the proportion of Australia is about 54%."

And I came across:

"In 1993, 23% of Australia's land was publicly owned (table 14.20). Over half of this public land (54%) was vacant crown land" - ABS (couldn't find any more recent in ABS

Looks like it's 15% now public, but note:

"Pastoral leases cover 44% of Australia, according to Austrade. Pastoral leases are defined by Austrade as a title issued for the lease of an area of crown land to use for the limited purpose of grazing of stock and associated activities."

So not allowed to use for anything other than that (land can't be used for housing).

"About 40% of Australia is covered by native title, in both exclusive and shared title. Australian government reports state that Indigenous communities hold the freehold title to 17% of the country, mainly in the Northern Territory and South Australia."

TL;DR

"Guardian Australia’s definition of Indigenous tenure, for mapping purposes, includes exclusive-possession native title and freehold, which confer the right to exclude others from the land. This amounts to about 26% of Australia’s landmass. "

"15% publicly owned"

"Pastoral leases cover 44% of Australia"

85% of Australias land mass basically not available for housing/private ownership.

10.5% private. 4.5% unknown.

* "About 40% of Australia is covered by native title, in both exclusive and shared title."

** "When non-exclusive native title is included, the proportion of Australia is about 54%."

Last edited:

I agree with your statement of the libertarian position on native land ownership (or land ownership in general). We also need to remember that talk of aboriginal land rights is not a collective claim but the claim of individual people who may possibility have been disposed of their land. Land grants to aboriginal groups do not provide restitution to individuals (or their descendants) who have been harmed but rather represent transfers of wealth to institutional actors who use this wealth to entrench their own position. You could be cynical and suggest that the state benefits from this virtuous circle, the problem never goes away but now we have a permanent woke voice to marginalise the majority and make us all feel guilty.Walter Block recently wrote this as well: https://www.econlib.org/who-really-owns-the-united-states/

And I came across:

Looks like it's 15% now public, but note:

So not allowed to use for anything other than that (land can't be used for housing).

TL;DR

85% of Australias land mass basically not available for housing/private ownership.

10.5% private. 4.5% unknown.

* "About 40% of Australia is covered by native title, in both exclusive and shared title."

** "When non-exclusive native title is included, the proportion of Australia is about 54%."

I will vote “No”

by Viv Forbes and many Friends

Australians are being asked to approve a permanent change to our constitution which is racist in intent and divisive in effect. Here is our cartoon on the subject by Steve Hunter:

Feel free to publish or pass around with no alterations.

No humans evolved here in Australia – our ancestors all came from somewhere else. The literal meaning of “indigenous” is “born here”, so most of us are indigenous. To try to divide indigenous Australians on the basis of skin colour or length of ancestry is more about politics than justice or good government. We are all Australians and we should never contemplate constitutional changes that promote and solidify racial division.

I am voting “No” because this proposal is going in the wrong direction and is serving other agendas.

There are many reasons to vote NO:

Further Reading:

by Viv Forbes and many Friends

Australians are being asked to approve a permanent change to our constitution which is racist in intent and divisive in effect. Here is our cartoon on the subject by Steve Hunter:

Feel free to publish or pass around with no alterations.

No humans evolved here in Australia – our ancestors all came from somewhere else. The literal meaning of “indigenous” is “born here”, so most of us are indigenous. To try to divide indigenous Australians on the basis of skin colour or length of ancestry is more about politics than justice or good government. We are all Australians and we should never contemplate constitutional changes that promote and solidify racial division.

I am voting “No” because this proposal is going in the wrong direction and is serving other agendas.

There are many reasons to vote NO:

- No humans evolved in Australia – the pioneers all came from somewhere else, usually on things that floated. And rock art in the Kimberlies and other relics tell us that the current aboriginals were not the first humans to occupy this land.

- Despite having “native title” to far more land per head of population than all other Australians, tribal aboriginals often live in degraded communal enclaves with poor community protection especially for women and children.

- We need to question closely anything promoted so strongly by their ABC, QANTAS plus big banks, big business, big miners, the bureaucracy, the ALP/Green/Teal coalition and the Communist Party.

- Political power should not be granted to one race of Australians – Australia is now home to Aboriginals, Islanders, English, Scottish, Irish, Welsh, Dutch, Italian, German, Scandinavians, Melanesians, Greek, Kiwis, Afghans and Africans, plus other Europeans, Asians, and Africans. Most have made permanent homes here. All who embrace Australian citizenship should be treated equally before the law.

- This Voice proposal would make a permanent racial division in Australia. But how will the favoured race be continually identified? Will the chosen people or the more recent “invaders” need to be tattooed? Or will DNA evidence be needed to prove racial identity?

- People identifying as Aboriginals already have more representation in Parliament than their numbers would justify. They already have several voices.

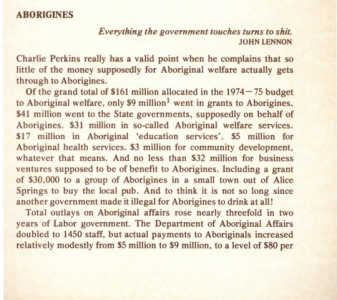

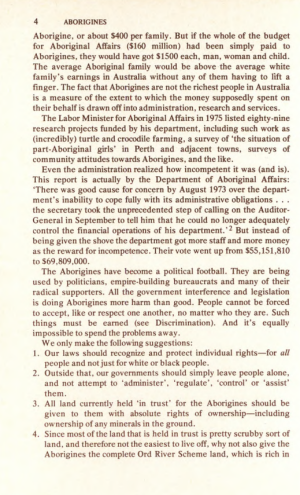

- Huge government departments and billions of dollars are already representing aboriginal interests, but their conditions do not improve.

- We have noted how some Australians are already being banned from certain tourist spots, private landowners feel threatened by the relentless advance of “Native Title”, and explorers find Sacred sites and Rainbow Serpents appearing on promising mineral discoveries and along infrastructure sites and routes.

- We are continually annoyed to be “welcomed” to every big event by people stomping around in red nappies, blowing smoke and making drainpipe noises. Most of these ceremonies are modern inventions. We do not need to be welcomed to our own country.

- We note with annoyance that place names are being changed suddenly and without warning or consultation. Imagine what is in store for names like Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Brisbane, Sydney, Melbourne, Adelaide and Cooktown. Or King George Square? And what about the nation of “Australia” that was created in 1901? Already the red and black flag is being flown next to the Australian Flag.

11. Their ABC has managed to alienate every bit of land as “land of the XXX People”. That has just alienated the rest of us.

12. There never was “an aboriginal nation” – just many tribes each subject to unwritten tribal law. Will the Voice be called to adjudicate tribal disputes?

13. We are already seeing certain books that report inconvenient history or anthropological records are disappearing from public libraries. Will the Voice be deciding what we are allowed to read?

14. “The Voice” would soon be clamouring for treaties, reparations and seizure of more lands. However, Aboriginals would not get individual freehold titles - just communal ownership where some elders control everything. Property owned by everyone is cared for by no one.

15. The most recent aboriginal migrants brought their dogs (dingoes) to Australia. They are now protected in many areas. But our horses, donkeys, sheep, cattle, camels and buffalo are “ferals” to be eliminated.

16. Giving a special “Voice” to people of a certain skin colour or genetic history will just promote everlasting division and hatred. It aims to separate and give special privileges to certain people and their descendants forever.

17. We must VOTE NO.

Further Reading:

- We already have a Voice

- See Kamahl being bullied because he changed his mind as he learned more:

- “Are We Indigenes Yet?”

- The first Aboriginal “Voice” in the Australian Parliament was Senator Neville Bonner elected in 1971. There are now eleven of them which is an over-representation of Voices. Why do we need another Voice, and who will decide what it says?

- Some 85,000 people have recently “identified” as aboriginal. Maybe we should all enrol here?

- It is all about Power and requires re-writing of history

- They already have a voice: “The National Indigenous Australians Agency”.

- Revenue from Government: $268M

- Employee Benefits: $163M

- What is it all about?

- Alan Jones on Indigenous Activists:

- Aboriginal Woman Kerry White says “NO”:

- What is this Referendum about?:

- The Hatred from some Voice advocates: https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/langton-1200x675.jpg

- The Push Back against Voice Vilification: https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/lion-flag.png

- Captain James Cook - the Great Invader? https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/cook.jpg

- Uluru Statement - One page or 26 pages? https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/uluru-1200x801.jpg

- John Anderson on the Voice and the Constitution: https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/the-voice-1200x867.jpg

- How to Fool the Experts: https://youtu.be/oVlFs9tfNPo

- The Voice? “I’m Over it”

- Geoffrey Blainey on the Voice

- Paying for the Land you are on: https://saltbushclub.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/canadian-receipt.jpeg

- The Voice – all about Power

- One More Indigenous Voice?

Patrick Danneskjold

LA Member

Democracy is meant to be one man one vote. With all the problems of democracy (tyranny of the majority etc), privileging one group of people with a voice in this way will only make democracy even worse and be contrary to the principle of one man one vote.

Worth highlighting this perspective though, would certainly be interested in applied similarly to Aboriginals.

Enforcement of private property rights in primitive societies: law without government

“The Kapauku had no formal government with coercive power. Most observers have concluded that there was a virtual lack of leadership among these people.

One Dutch administrator noted, however, that "there is a man who seems to have some influence upon the others. He is referred to by the name tonowi which means ‘the rich one.’ Nevertheless, I would hesitate to call him a chief or a leader at all; primus inter pares [the first among equals] would be a more proper designation for him.”[73] In order to understand the role and prestige of the tonowi, one must recognize two basic values of the Kapauku: an emphasis on individualism and on physical freedom. The emphasis on individualism manifested itself in several ways. For instance, a detailed system of private property rights was evident. In fact, there was absolutely no common ownership. “A house, boat, bow and arrows, field, crops, patches of second-growth forest, or even a meal shared by a family or household is always owned by one person. Individual ownership… is so extensive in the Kamu Valley that we find the virgin forests divided into tracts which belong to single individuals. Relatives, husbands and wives do not own anything in common. Even an eleven-year-old boy can own his field and his money and play the role of debtor and creditor as well.” [75]

The paramount role of individual rights also was evident in the position of the tonowi as a person who had earned the admiration and respect of others in the society. He was typically “a healthy man in the prime of life” who had accumulated a good deal of wealth.[76] The wealth accumulated by an individual in Kapauku society almost always depended on that individual’s work effort and skill, so anyone who had acquired sufficient property to reach the status of tonowi was generally a mature, skilled individual with considerable physical ability and intellectual experience. However, not all tonowi achieved respect that would induce others to rely upon them for leadership. “The way in which capital is acquired and how it is used make a great difference; the natives favor rich candidates who are generous and honest. These two attributes are greatly valued by the culture.”

Generosity was a major criteria for acceptance of a particular tonowi in a leadership role because, in large part, followers were obtained through contract. Each individual in the society could choose to align himself with any available tonowi and then contract with that chosen tonowi. Typically, followers would become debtors to a maagodo tonowi (a “really rich man”) who was considered to be generous and honest. In exchange for the loan, the individual agreed to perform certain duties in support of the tonowi. The followers got much more than a loan, however:

Tonowi authority was given, not taken. This leadership reflected, to a great extent, an ability to ”persuade the unit to support a man in a dispute or to fight for his cause.“[79] Thus the tonowi position of authority was not, in any way, a position of absolute sovereignty. It was achieved through reciprocal exchange of support between a tonowi and his followers, support that could be freely withdrawn by either party (e.g., upon payment of debt or demand for repayment).[80]

What happened if a tonowi proved to be ineffective or dishonest in his legal role? First of all, honesty and generosity were prerequisites for a tonowi to gather a following. However, if someone managed to do so and then proved to be a bad leader, he simply lost his following. "Passive resistance and refusal of the followers to support him is… the result of a decision [considered unjust].”[81] Clearly, change in the legal authority was possible; indeed, one purpose of the Kapauku procedure that involved articulation of relevant laws by the tonowi was to achieve public acceptance of his ruling. As Fuller noted, one course of “the affinity between legality and justice consisted simply in the fact that a rule articulated and made known permits the public to judge its fairness.[82] The informality and contractual characteristics of Kapauku leadership led many western observers to conclude that Kapauku society lacked law, but clear evidence of rules of recognition, adjudication, and change can be demonstrated within the Kapauku’s legal system.”

— Bruce L. Benson, https://mises.org/library/enforcement-private-property-rights-primitive-societies-law-without-government

Enforcement of private property rights in primitive societies: law without government

“The Kapauku had no formal government with coercive power. Most observers have concluded that there was a virtual lack of leadership among these people.

One Dutch administrator noted, however, that "there is a man who seems to have some influence upon the others. He is referred to by the name tonowi which means ‘the rich one.’ Nevertheless, I would hesitate to call him a chief or a leader at all; primus inter pares [the first among equals] would be a more proper designation for him.”[73] In order to understand the role and prestige of the tonowi, one must recognize two basic values of the Kapauku: an emphasis on individualism and on physical freedom. The emphasis on individualism manifested itself in several ways. For instance, a detailed system of private property rights was evident. In fact, there was absolutely no common ownership. “A house, boat, bow and arrows, field, crops, patches of second-growth forest, or even a meal shared by a family or household is always owned by one person. Individual ownership… is so extensive in the Kamu Valley that we find the virgin forests divided into tracts which belong to single individuals. Relatives, husbands and wives do not own anything in common. Even an eleven-year-old boy can own his field and his money and play the role of debtor and creditor as well.” [75]

The paramount role of individual rights also was evident in the position of the tonowi as a person who had earned the admiration and respect of others in the society. He was typically “a healthy man in the prime of life” who had accumulated a good deal of wealth.[76] The wealth accumulated by an individual in Kapauku society almost always depended on that individual’s work effort and skill, so anyone who had acquired sufficient property to reach the status of tonowi was generally a mature, skilled individual with considerable physical ability and intellectual experience. However, not all tonowi achieved respect that would induce others to rely upon them for leadership. “The way in which capital is acquired and how it is used make a great difference; the natives favor rich candidates who are generous and honest. These two attributes are greatly valued by the culture.”

Generosity was a major criteria for acceptance of a particular tonowi in a leadership role because, in large part, followers were obtained through contract. Each individual in the society could choose to align himself with any available tonowi and then contract with that chosen tonowi. Typically, followers would become debtors to a maagodo tonowi (a “really rich man”) who was considered to be generous and honest. In exchange for the loan, the individual agreed to perform certain duties in support of the tonowi. The followers got much more than a loan, however:

It is good for a Kapauku to have a close relative as headman because he can then depend upon his help in economic, political, and legal matters. The expectation of future favors and advantages is probably the most potent motivation for most of the headman’s followers. Strangers who know about the generosity of a headman try to please him, and people from his own political unit attend to his desires. Even individuals from neighboring confederations may yield to the wishes of a tonowi in case his help may be needed.“

Tonowi authority was given, not taken. This leadership reflected, to a great extent, an ability to ”persuade the unit to support a man in a dispute or to fight for his cause.“[79] Thus the tonowi position of authority was not, in any way, a position of absolute sovereignty. It was achieved through reciprocal exchange of support between a tonowi and his followers, support that could be freely withdrawn by either party (e.g., upon payment of debt or demand for repayment).[80]

What happened if a tonowi proved to be ineffective or dishonest in his legal role? First of all, honesty and generosity were prerequisites for a tonowi to gather a following. However, if someone managed to do so and then proved to be a bad leader, he simply lost his following. "Passive resistance and refusal of the followers to support him is… the result of a decision [considered unjust].”[81] Clearly, change in the legal authority was possible; indeed, one purpose of the Kapauku procedure that involved articulation of relevant laws by the tonowi was to achieve public acceptance of his ruling. As Fuller noted, one course of “the affinity between legality and justice consisted simply in the fact that a rule articulated and made known permits the public to judge its fairness.[82] The informality and contractual characteristics of Kapauku leadership led many western observers to conclude that Kapauku society lacked law, but clear evidence of rules of recognition, adjudication, and change can be demonstrated within the Kapauku’s legal system.”

— Bruce L. Benson, https://mises.org/library/enforcement-private-property-rights-primitive-societies-law-without-government

Similar threads

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 322

- Replies

- 1

- Views

- 552